I first read many years ago, perhaps more than once, this classic novel of paranoia, gaslighting and what John Clute, when he and I were doing The Encyclopedia of Fantasytogether, christened godgaming — the process whereby a usually malicious person or group persuades another or others that a fictitious reality is what’s actually going on. (The godgaming type-novel is John Fowles’s The Magus.) More recently, in 2014, I watched Nunnally Johnson’s screen adaptation of it, Black Widow (1954), with the splendid Van Heflin as Peter, Ginger Rogers as Lottie, Gene Tierney impeccably cast as Iris and Peggy Ann Garner as Nanny Ordway.

Broadway producer Peter Duluth’s actress wife Iris is out of town for a while visiting her ailing mother. Peter is induced to go to a party held by their overweening upstairs neighbors, belle dame actress Lottie Marin and her subjugated husband Brian. There he meets Nanny Ordway, a young wannabe writer who seems like a fish out of water. Because he’s lonely and she’s broke and hungry, he takes her out for a burger. They see each other a few more times, always strictly platonically, and finally he lends her the key to the Duluth apartment so she can write there during the day, while he’s out, rather than try to do so in the dumpy Greenwich Village bedsit she shares with another girl.

It never dawns on him that others might regard his friendship with Nanny rather differently until, on Iris’s return, they go back to the apartment from the airport to find Nanny dangling from the chandelier in the master bedroom, having apparently hanged herself. Even then Peter doesn’t really recognize the hazard of his situation until it’s revealed that Nanny was both pregnant and murdered. Furthermore, everyone heard from Nanny’s own lips that she was engaged in a passionate affair with Peter . . .

In a way it’s a pity that whoever of the various partnerships who used the rubric “Patrick Quentin” chose to employ the series character Peter Duluth in the main role rather than making this a standalone, because there are times when it seems absolutely pellucid that, despite his innocence, Peter has no escape from the predicament that has so deftly been stitched around him — that he’s destined for the Big House or more likely the chair. Or perhaps it’ll prove to be the case that he’s been lying through his teeth to us, his readers? Of course, we know that neither of those can be the outcome because there are other Peter Duluth novels to come.

(He might lose Iris, though, as he almost did in A Puzzle for Fools, so there’s at least that level of uncertainty left.)

In the end everything’s neatly worked out, as we knew it would be, with Peter solving the bulk of the mystery himself only to discover that the NYPD’s Inspector Trant, whom he’s been regarding as a foe, has not only gotten there before him but also worked out the real truth, which is somewhat beyond the explanation that Peter achieved.

So far I haven’t come across a Patrick Quentin novel that doesn’t stand up well under rereading or, if being read afresh, hasn’t stood up well to the passage of time. The social attitudes in the books are, too, often surprisingly open for their day; in Black Widow, for example, the most intelligent and likable of the witnesses whom Peter interviews is a hatcheck girl/waitress, Anne, about whom he reflects that it’s purely because of the color of her skin that her existence is relatively so humble — a pleasingly human reaction in 1952 America, where the lynch mobs were still active.

I also liked the openness about sexuality. To be plain, there’s nothing remotely raunchy in the book, yet at the same time it’s manifest that intimacy plays an important role in Peter and Iris’s marriage, that extramarital sex is commonplace in their milieu, and that adultery, while frowned upon, is not necessarily some sort of precipice from which there’s no retreat — that it may even be, on rare occasion, morally acceptable. (I can’t go further into this issue for fear of spoilers.)

What also remains undated is the Patrick Quentin narrative style, which remained remarkably unchanged from one novel to the next despite any changes of writing personnel. Always completely under control, it has a kind of coolness of tone, a sense of objectivity that makes what are often the most dramatic of actions and emotional turbulences all the more affecting. Here I was completely involved in Peter’s emotional helterskelter as the noose seemed to be tightening around his neck, while also sympathizing fully with his plight: like I assume most of us, I’ve been in situations where outsiders have irritatingly misconstrued friendships as something else. Thank my lucky stars I’ve never encountered a Nanny Ordway in such circumstances, though!

Because it’s so very smoothly and elegantly written, and because it’s so engrossing, Black Widow, a short novel by today’s standards, is a remarkably quick read. In case you haven’t guessed, I think it’s spiffy.

Reblogged this on Ed;s Site..

Pingback: book: Black Widow (1952; vt Fatal Woman) by Patrick Quentin – Ed;s Site.

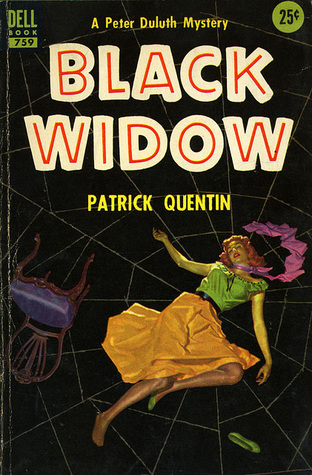

I have the same edition that you have pictured and it’s a nice piece of work. I’m leaning towards reading this as my next Patrick Quentin, although I’ve only read one Duluth (Puzzle for Players) and one Trant (Death and the Maiden). Any thoughts as to whether there’s continuity on the story lines that would be important before reading this one? I get that the relationship with Iris is obviously a point of continuity. Should I hold off?

I’m probably the last person in the world to ask about this! I’ve never gone through series in chronological order — just read the novels as the whim struck me. I can’t think there’s anything in Black Widow that’d be a spoiler except the bit alluded to about their marriage having suffered a rocky patch a while back that it survived. But then just glancing at the books’ blurbs would reveal that.

Most of the collaborators in the “Patrick Quentin” partnership were gay, at a time when active homosexuality was illegal, which explains their indifference to conventional sexual norms of the time. “The Passing Tramp” website has interesting discussions of the books and their creators – it was there that I became interested in them.

I’d thought it was just Wheeler and Webb who were gay, rather than “most”! It did occur to me that the gayness of the two principal Quentins could well explain the open sexual mores that you generally find in the novels; but I think I’m right in recalling that they mixed with the theatrical lot in NYC, which could equally well explain it, the acting profession having traditionally had a far more sexually tolerant tradition — especially since in this particular novel there aren’t any gay characters. (I can’t remember if there are in any of the others.)

I read Curt’s stuff on the Quentins — interesting, as his essays invariably are.

Hmm, another one to consider. Strangely appealing, which is a more positive reaction from me than I expected.

If you haven’t read any PQ, I’m sure you’d find a very great deal; to like in “his” work.

Ah yes, the great “Patrick Quentin” (which in this case was Wheeler writing solo). I remain a huge fan and it does seem that the Q Patrick / Stagge / Quentin novels and stories are getting some belated recognition, which really i s good thing.

I hadn’t realized PQ had dropped out of the GAD-reading public’s eye until I read as much on a GAD blog the other day. So far as I’m concerned, PQ has always been one of the greats.

I’m in a way surprised to hear this one was by Wheeler solo. If forced to guess, I’d have said Webb & Wheeler.

I know what you mean – if you compare it with the next, and last, Duluth story (MY SON, THE MURDERER) the difference is quite stark with a much strong emphasis on character and a loosening of the plot. I wonder if the basic plot nugget, the neat deception on which FATAL WOMAN hangs, did belong to Webb but stylistically I can see that the Wheeler influence is great. When I got into ‘their’ work in the early 1980s the received wisdom was that the Wilson and Webb partnership ended in 1952 but it now seems it was really the late 1940s. But then I didn’t know then that theirs was a personal partnership as well as professional, so I dare say lines can get blurred. Curtis Evans seems very sure about his dates though – I am really, really curious to read his work on the “author”.

I’m not sure I’ve read My Son the Murderer; I’ll have to see if I my library system has a copy. The one I’d be really keen to get hold of, out of sheer curiosity, is the Aswell solo thriller. Likewise the Stagges.

I think I read that one in Italian (it was also published as “THE WIFE OF RONALD SHELDON” by the way). The best of the Wheeler books is probably THE MAN WITH TWO WIVES, which i must re-read. I’m a big, big fan of the Stagges. As a fan of Carr I really lapped them up as a kid. Been a while since I read any of them, must admit.

it was also published as “THE WIFE OF RONALD SHELDON”

Ah! Under which title I read it, back in the day. Can’t remember much about it, though. Same goes for The Man with Two Wives; thanks for the tip that I should reread it sooner rather than later.

And so the Stagges are like Carr, you’re saying?

Yes, in the sense that the Stagge books emphasise a dark and brooding atmosphere which often make the cases seem potentially “impossible” – even supernatural (TURN OF THE TABLE, aka FUNERAL FO FIVE, deals explicitly with spiritualism as I recall)

Hm. I see some of them have been ebooked. I think my exploration may start sooner rather than later . . .

Interesting review! This one wasn’t on my radar, but it is now. The only Patrick Quentin title I have read is 1959’s Shadow of Guilt. Like other respondents, the Q. Patrick/PQ/Jonathan Stagge are recent discoveries for me, but it’s nice to hear that they have been part of your genre reading for a while. They are worth discovering or re-discovering. All best —

Yes. As I think I mentioned to someone else here, I was surprised to discover relatively recently that the PQs had been neglected over the years: I just assumed everyone else knew about them, was reading/had read them, and held them in the same sort of respect as I did. I’m glad to hear you’re just embarking on a voyage of discovery with PQ and QP and JS!

I also recently discovered that there were far more of the team’s novels left for me to read than I’d thought — some of them may not not have made their way to the UK, which is where I did most of my initial PQ reading. So that means I have an adventure ahead as well!

As I prefer 1930s mysteries to post-1950 ones in general, I’ve read a few more Q. Patrick titles than I have Patrick Quentin. But I shall keep reading, regardless of the pseudonym and publication date! Glad you have more to discover — enjoy the journey, and I look forward to your reviews —

Thanks for the good wishes, Jason!

I’ve seen the film, which seemed rather theatrical in its staging. Had no idea it was based upon one novel in a series.

I’d agree with you about the staging of the movie. It seems apposite in terms of the theatrical milieu in which the tale is set, so I assume it was deliberately done.

In reply to Cavershamragu (this reply was “invisibled” by WordPress’s poxy template):

it was also published as “THE WIFE OF RONALD SHELDON”

Ah! Under which title I read it, back in the day. Can’t remember much about it, though. Same goes for The Man with Two Wives; thanks for the tip that I should reread it sooner rather than later.

And so the Stagges are like Carr, you’re saying? Hm.